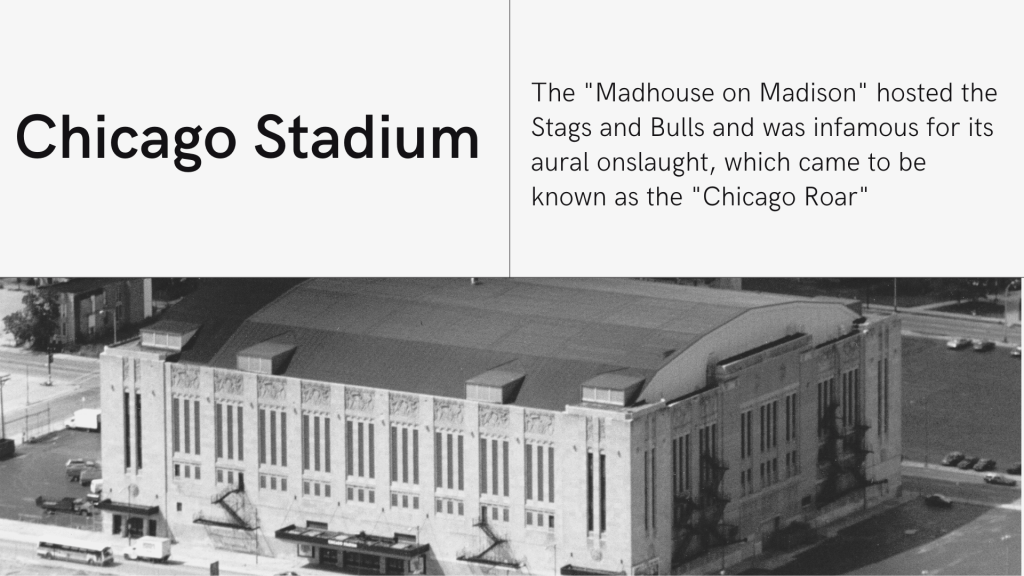

1) Chicago Stadium (Chicago)

When CNN provided a live broadcast of Chicago Stadium being demolished in 1995 to build a parking lot for its replacement, the camera panned to local fans weeping at the sight. How does a simple building invoke such a strong emotional reaction? Nicknamed “The Madhouse on Madison” for its claustrophobic feel, overtly loud acoustics, and location on West Madison Street, the arena became indelibly linked with raucous Chicago culture. It was the largest arena in history when it was built in 1929 and its uniquely cavernous, barn-like architectural features rendered it especially intimidating (as did its first-of-its-kind air conditioning system, which frequently broke down and filled the arena with fog during games). Chicago Stadium mainly hosted only the NHL’s Blackhawks for much of its run but eventually added the early NBA franchise the Stags, and later the Bulls for almost three decades. It was the site of the Bulls’ first three championships with Michael Jordan, who now displays the arena’s center court logo in his North Carolina home. It was replaced in 1994 by the United Center, whose architects took special care to attempt to recreate the conditions of the infamous “Roar” that Chicago fans could create in the original arena.

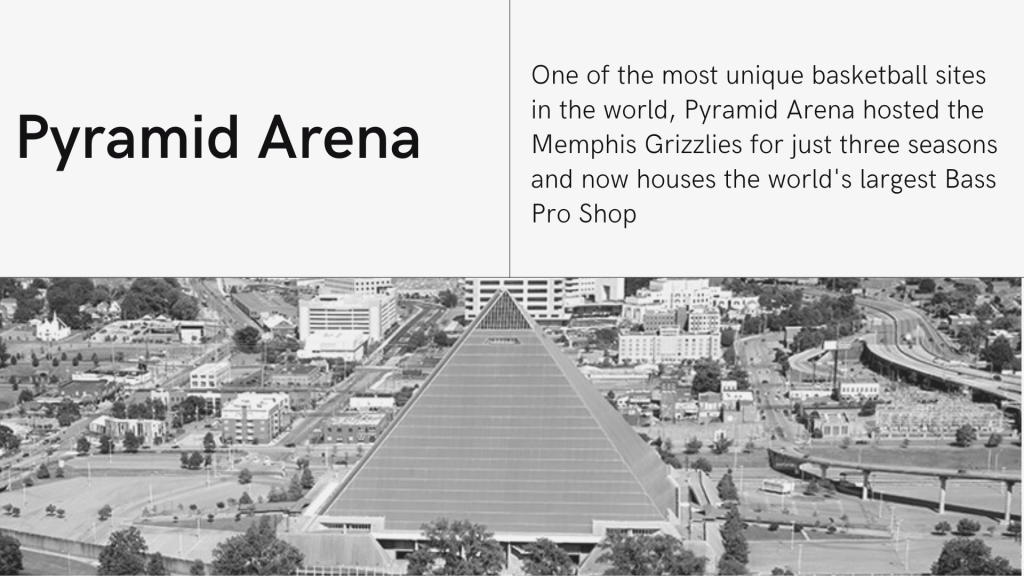

2) Pyramid Arena (Memphis)

Originally conceived as an entertainment complex/college football museum/indoor theme park, the “Great American Pyramid” in Memphis instead became a basketball arena after its original owner went bankrupt. Designed to evoke the famous landmarks of the Tennessee city’s Egyptian namesake, the stainless steel structure technically became the third tallest pyramid in the world when it began hosting Memphis Tigers basketball in 1991. Its imposing outside structure and vertical stands lent it the nickname “Tomb of Doom” both for its intimidation factor on opposing teams but also for the acrophobia it could render on fans unlucky enough to be seated near the top. When the Grizzlies were lured to town from Vancouver in 2001, one of the conditions of their re-location was that they’d spend just three years in the Pyramid Arena while a new, permanent home was built. Thus, an extraordinary and expensive basketball site was already obsolete just one decade into its existence, as the Grizzlies and Tigers moved to the FedEx Forum in 2004. The building lay dormant for over a decade, almost becoming a megachurch, a casino, or a Grammy Hall of Fame, before finally re-opening in 2015 as the world’s largest Bass Pro Shops superstore, with features including an archery range, aquarium, laser arcade, hotel, bowling alley, restaurants, and the tallest freestanding elevator in America.

Our first volume will be published throughout the ’18-’19 NBA season

3) Memorial Coliseum (Portland)

Unlike most of the arenas on this list, the 62-year-old Memorial Coliseum is still standing and still functional for basketball. In fact, the Trail Blazers had returned to it for exhibition games twice, once in 2009 for the franchise’s 40th anniversary and again in 2019 for the 50th. Nicknamed “The Glass Palace” for its tall, grey outer glass walls, Memorial Coliseum opened in 1960 but didn’t host basketball until the Trail Blazers joined the NBA as an expansion franchise a decade later. Though they moved into their current location, the Rose Garden Arena (now called the Moda Center) back in 1992, fans still pine for the original home and why not? It was the site of all three Portland NBA Finals appearances. That includes their lone championship back in 1977, which they clinched on that home floor in thrilling fashion, leading to the court being stormed by the Blazers faithful. Though it now mostly hosts minor league hockey, cheerleading competitions, and concerts, the Memorial Coliseum is a Portland institution and treated as such. When a minor league baseball team proposed tearing it down in 2005 to make way for a new ballpark, locals successfully rallied to get the coliseum protected status in the National Register of Historical Places.

4) Philadelphia Civic Center (Philadelphia)

5) The Spectrum (Philadelphia)

It played host to the Philadelphia Warriors for 10 seasons, including their 1956 NBA championship, and the 76ers for four seasons, but pro basketball is a mere footnote in the history of the Philadelphia Civic Center. Opened in 1931, the art deco structure earned its nickname over the years as “The Nation’s Most Historic Arena,” hosting four national Democrat or Republican conventions, notable speeches from Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, and others, and a Beatles concert during their first American tour. When the Philadelphia Flyers were announced as an NHL expansion franchise in 1967, the city knew it needed a more modern arena and thus The Spectrum was built. The name was meant to invoke the full spectrum of events that could be held there, but it was also an acronym, standing for SPorts Entertainment Circus Theatricals Recreation, and UM as in “um, what a nice building!” While the Flyers built their reputation there as the “Broad Street Bullies,” the 76ers found their own success in the building, including an NBA championship in 1983. It was ditched by the 76ers and Flyers in 1996 for the newly opened CoreStates Center, now called the Wells Fargo Center. There were still events happening at The Spectrum until 2008, when it was officially closed and then demolished soon after at an event featuring Julius Erving amongst other Philly sports luminaries. As for the Philadelphia Civic Center, it also continued to operate for college basketball and concerts until 1996, when the CoreStates Center rendered it fully obsolete. It was demolished in 2005, ending a run of 74 years for a Philadelphia icon.

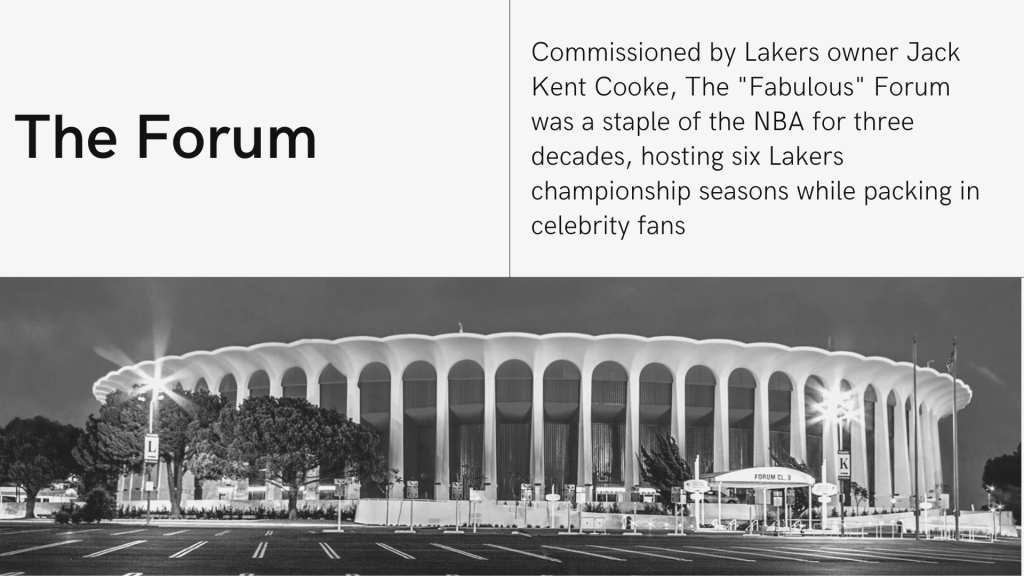

6) The Forum (Los Angeles)

In a city that already had a Coliseum for football, it made sense to build a Forum for basketball. Opened in 1967 in Southwestern L.A., The Forum (which is still colloquially called “The Fabulous Forum” by locals and officially called “The Great Western Forum” for much of its lifetime due to a licensing deal) was funded by Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke, who was tired of paying the lease on the team’s former home, the Memorial Sports Arena. It was a modern technological marvel, not just for its awe-inspiring outer design but also its unique roof and column structures which allowed basketball fans (and Kings hockey fans, concert-goers, etc.) perfect, unobstructed views. When Cooke sold the team and arena to Jerry Buss in 1979, the Forum became one of the city’s ultimate hot spots, with celebrities lining up to catch Showtime era Lakers games, sometimes court side and sometimes up in the luxurious owner’s box. It was also the site of the basketball tournament in the 1984 Olympics and the home of Wayne Gretzky for several years after he was traded to the Kings. Though the Lakers have now been gone for over two decades, relocating to the Staples Center in downtown L.A. in 1999, The Forum still stands and hosts concerts, boxing matches, award shows, and other major events. It was purchased by Clippers owner Steve Ballmer in 2020, so as to avoid a legal battle over building a new arena for his franchise.

7) Palace of Auburn Hills (Detroit)

At the start of the last decade, circa 2010, there were only two NBA arenas still left without sponsored naming rights. One was Madison Square Garden, the self-proclaimed “most famous arena in the world.” The other was the Palace of Auburn Hills, opened in 1988 about 30 miles north of Detroit to host the Pistons. Before finding this iconic home, the Pistons had been a wayward franchise, playing in numerous venues in and around Detroit, including a decade in the cavernous Silverdome. Privately financed by then Pistons owner Bill Davidson, The Palace was both versatile and extravagant, with a large cache of luxury suites that set the stage for modern arena design. The Pistons won the NBA title in each of their first two seasons in The Palace, then added a third title in 2004. But the arena’s inconvenient location in the suburbs eventually became a liability and the Pistons moved back to downtown Detroit in 2017, into the newly built Little Caesars Arena. Though the Palace was still in solid condition, it failed to find a new tenant and was demolished in 2020 to make way for an office park. It was the true end of an era for NBA arenas, as it was one of the last standing examples of private financing and lack of corporate sponsorship.

A visual history of legendary NBA arenas

8) Onondaga War Memorial Arena (Syracuse)

Unlike The Palace of Auburn Hills or The Spectrum, which were demolished soon after their NBA tenants departed, the Onandaga War Memorial Arena has continued use for almost 60 years now since the Syracuse Nationals left town. Opened in 1951 to host the Nationals, who just two years prior had merged into the NBA from the NBL, as well as the Syracuse Orange and the minor league hockey team the Syracuse Warriors, the War Memorial Arena held close to 9,000 fans for sports, which was high for the era. It was the site of the Nationals’ thrilling NBA Finals victory in 1955, clinching game seven on their home floor over the Pistons in the waning moments, and the All-Star Game in 1961. After the Nationals packed up and left for Philadelphia in 1962, the War Memorial Arena remained active over the ensuing decades thanks to numerous minor league hockey and indoor soccer franchises, plus concerts, high school sports championships, and pro wrestling events. It was listed in the National Register of Historical Places in 1988 and has received two major renovations since then. In fact, it made news in 2019 by securing a new sponsorship deal, giving the arena its new unwieldy official name of Upstate Medical University Arena at Onandaga County War Memorial.

9) Alamodome (San Antonio)

Inspired by nearby Houston’s legendary Astrodome and hoping to lure a new or relocating NFL team, San Antonio unveiled the Alamodome in 1993. That football franchise never materialized but the stadium would soon become an unlikely longtime home for the Spurs. Stuck for years prior in the HemisFair Arena, which at one point literally raised its roof just to increase its capacity from 10,000 fans to 16,000, Spurs owner Red McCombs was continually lobbying the city for a larger site. Like a monkey’s paw curling to indicate “be careful what you wish for,” his team was placed in a spacious football field. Yes, the Alamodome had its charms, most notably the oversized curtain that blocked half the stadium while the remaining half was fitted with a basketball court (the empty side was typically used for broadcast crew set-up and logistics). It also provided a capacity more than twice that of the HemisFair, with a peak of almost 40,000 fans in attendance for the 1999 NBA Finals. But it was an operational nightmare and the Spurs’ jerry rigged court setup prevented the stadium from hosting much else during basketball season. Just a couple years after clinching the first NBA title in franchise history, the Spurs moved into a more traditional arena, the SBC Center (now called the AT&T Center). Though it’s mostly stuck to hosting football (most notably the yearly NCAA Alamo Bowl), soccer, and concerts in the last couple decades, the Alamodome has still been the site of the occasional basketball game, including the 2018 NCAA Final Four, when the more modern “center of the field” court configuration was used, allowing over 70,000 fans to attend.

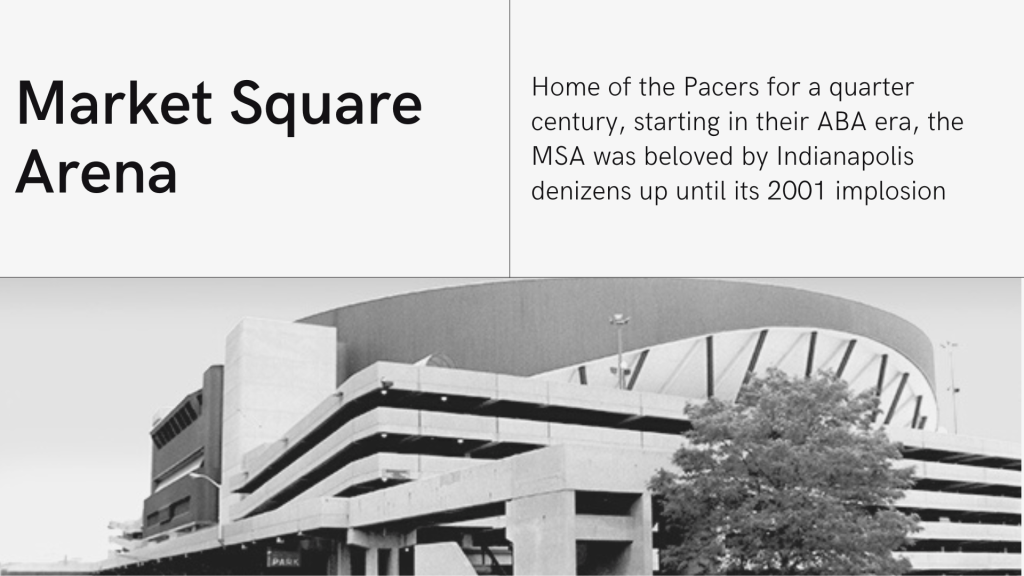

10) Market Square Arena (Indianapolis)

Built in 1974 to revitalize downtown Indianapolis and give a home to the Pacers, then based in the ABA (plus a new World Hockey Association (WHA) team called the Racers), Market Square Arena was a centerpiece of the city for 25 years. It can lay claim to two incredible, non-basketball milestones in its first five years: It was the site of Elvis Presley’s final concert, a 1977 show just a few weeks before his death, and it was the first venue of Wayne Gretzky’s pro hockey career, in a 1978 WHA game with the Racers. Perhaps befitting Pacers history, the most notable basketball moment in the arena’s history arguably involved an opposing player, as Michael Jordan started his 1995 comeback with a game in Market Square Arena. All that being said, there are fond memories for Pacers fans over the years of what they affectionately abbreviated as MSA. Though the Pacers never reached the NBA Finals there, they did play the 1975 ABA Finals in MSA, losing the series to the Kentucky Colonels. Like so many sports venues built before the ’80s, Market Square Arena was ultimately the victim of its lack of capacity for the luxury boxes and suites that define money making in modern arenas. The Pacers moved to Conseco Fieldhouse in 1999 and, almost tauntingly, finally made their first NBA Finals appearance that season, after losing in the Conference Finals in four of their final six years in MSA.

11) The Omni Coliseum (Atlanta)

Maybe it’s for the best but you just don’t see arenas like The Omni get built anymore. Opened in 1972 to host the Hawks (and the NHL expansion franchise Flames), who had spent their first four seasons in Atlanta playing at Georgia Tech’s Alexander Memorial Coliseum, The Omni was one of the most unique architectural sports structures in American history. From the outside, its supposedly “weather proofed” steel facade looked like a rusted, upside down egg crate and its seating arrangement was a novel rectangular shape with color-coded sections. It provided a distinct home court advantage for the Hawks not just in its acoustics but also in its amenities, or lack thereof. Visiting teams lamented its cramped locker room, complete with showers that were down the hallway from the lockers. In addition, the outside structure was unexpectedly pummeled by the Georgia humidity and was literally falling apart after a couple decades. In two final insults to the venue, the NHL deemed it unfit for another expansion franchise in the early ’90s and the 1996 Olympics basketball tournament was instead hosted partially at the smaller Forbes Arena and partially at a football stadium, the Georgia Dome. That football site became home of the Hawks starting in 1997, while they waited for the The Omni to be demolished and replaced. The new Philips Arena opened in 1999 and though it certainly has the conveniences and luxuries of a modern arena, it also lacks the perspicuous charms of The Omni.

12) Kemper Arena (Kansas City)

Built on the site of a former stockyards and financed mainly by its namesake, local fat cat R. Crosby Kemper, Kemper Arena opened in downtown Kansas City in 1972 to host the Kings, who had recently relocated from Cincinnati. It was the first major project of legendary architect Helmut Jahn and was considered a marvel when it first opened. But in 1979, a major storm caused the roof to collapse, forcing the arena to close for a year for repairs and the Kings to move back to their original Kansas City home, the ancient, cramped Municipal Auditorium. Though the Kings struggled through most of their tenure in the city, they did play host in the Western Conference Finals at the Kemper Arena in 1981, making a surprise appearance against the Rockets. In addition to the Kings, who eventually moved to Sacramento in 1985, Kemper Arena also played sometime host to an NHL franchise (the Kansas City Scouts), Major League Indoor Soccer franchise (Kansas City Comets), and an Arena Football League franchise (Kansas City Brigade). Probably the arena’s greatest moment for local sports fans came in 1988, when it was a virtual home site for the national champion Kansas Jayhawks in the Final Four.

13) KeyArena (Seattle)

When the KeyArena first opened in 1962, the SuperSonics were still years away from becoming an expansion franchise. The original basketball tenant in the arena, then called the Washington State Pavilion (and later the Seattle Center Coliseum), was the Seattle University men’s team. The venue became the site of the Sonics’ inaugural season in ’67-’68 and their only and one NBA title in 1979, though they clinched the Finals that year on the road in Washington. Like so many venues that were built in the ’60s and ’70s as American pro sports massively expanded, the Seattle Center Coliseum was woefully outdated by the early ’90s. In fact, it was the site of the only rain delay in NBA history, a 1986 match-up against the Suns where rain leaked through the roof onto the court, causing the game to be postponed for 24 hours. When a new arena deal fell through, there were heavy rumors that Sonics owner Barry Ackerley would relocate the franchise. Seattle mayor Norm Rice managed to swoop in and create a unique arrangement wherein the Seattle Center Coliseum would be stripped and rebuilt using its frame as a baseline using public bonds and a revenue sharing plan between the team and city. It re-opened as KeyArena in 1995 (naming rights were sold to KeyBank) and the Sonics reached the NBA Finals in their first season in the modernized venue. But that honeymoon period was a brief one, as Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz purchased the team in 2001 and almost immediately began lobbying the city for a publicly funded new arena. When the city refused, he sold the team to Oklahoma City’s Clay Bennett, who quickly relocated them to his hometown. KeyArena remained busy in the ensuing years, still hosting the Seattle Storm of the WNBA, Seattle University, plus the usual slate of concerts and events. With an NHL expansion franchise looming in 2017, the city of Seattle finally agreed to public funding to once again modernize KeyArea. When the redevelopment was complete, the naming rights were sold again, this time to Amazon, who dubbed it Climate Pledge Arena.

14) Boston Garden (Boston)

Synonymous in so many ways with the sport of basketball itself, the original Boston Garden was a mecca. It was the first, and ultimately only, attempt by legendary promoter Tex Rickard to build a “Garden” in all the major cities of the U.S. beyond the original Madison Square Garden in New York. Built with boxing in mind as the main attraction, the seats were unusually close to the action, which would eventually lend a serious advantage to the Celtics, who became tenants in their inaugural season starting in 1946. No arena has been the site of more NBA championship trophy celebrations than the Garden, with the Celtics clinching titles nine times in the building. Meanwhile, the only visiting team ever to clinch a championship in the Boston Garden was the Lakers in 1985. With its cramped seats, lack of air conditioning, unique parquet floor (which was installed in 1952), and general mystique, the Boston Garden had a reputation for decades as the most difficult road location in the NBA. It was also obviously outdated already by the early ’70s and local officials made numerous attempts over the years to replace it, all of which failed in legislation or negotiations until 1993, when both the Bruins and Celtics threatened to leave town without a new arena so construction finally began on a controversial replacement right next door. The vaunted Boston Garden had a farewell event in September of 1995, with luminaries like Larry Bird and Red Auerbach in attendance, while the parquet floor was cut into pieces, with some of it integrated into the new arena floor and some of it sold off as auctioned keepsakes. The Garden lay vacant for three years, like a ghostly apparition haunting its shiny, new neighbor, until it was torn down in 1998 to make way for luxury apartments.

Next up in Boston Garden

- Golden voices: Eight NBA announcers with retired microphones

- Slamming the door shut: 19 winner-take-all NBA playoff game blowouts

- Don’t you forget about me: 80 basketball moments from the ’80s that changed the sport forever

- Brand disloyalty: 12 ill-fated NBA arena naming rights deals

- Instant classics: 75 greatest games in NBA history

- Hallowed halls: 14 memorable arenas no longer in use by NBA teams

Next up in Franchise Events

- Foundational pieces: 30 notable NBA expansion draft picks

- All over the map: Eight times that the NBA realigned teams across conferences

- Golden voices: Eight NBA announcers with retired microphones

- The name game: 13 current NBA franchises that have changed names

- Don’t you forget about me: 80 basketball moments from the ’80s that changed the sport forever

- We built this city for pick and roll: 10 cities that have been rumored NBA franchise destinations

- Heart of the deal: 10 notable NBA franchise ownership changes

- Brand disloyalty: 12 ill-fated NBA arena naming rights deals

- Heading on down the highway: 14 current NBA franchises that have re-located

- Extracurricular activities: 75 off-court moments that shaped the NBA